Electric vehicles are a tiny but accelerating force in the U.S. passenger car market, and automotive suppliers are feeling the burn. Their original equipment manufacturer (OEM) customers—U.S. and foreign automakers—have laid out new platforms, introduced new models, built new plants and retrofitted old ones to prepare for an electric vehicle future.

The growing pains that come with the transition are especially tough on suppliers, who put forth much of the investment in new technology and whose strategies must account for automakers’ last-minute design changes, fluctuating production schedules and automaker shifts in priorities.

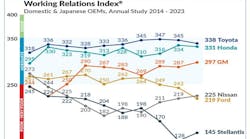

This year’s Supplier Working Relations Index (WRI)—an annual survey that measures how satisfied Tier 1 suppliers are with working with their OEM customers—reflects the uncertainties suppliers face around large investments they must make in new technology while still focusing on components for gas-powered vehicles. OEMs with the highest ratings in the survey tend to have better sourcing, production processes and results.

Ford, Toyota, Honda, Stellantis, General Motors and Nissan are, historically, the OEMs willing to share the information required to take part in the Plante Moran study, which they then use for benchmarking purposes. (Among those not participating in the survey: Volkswagen, BMW, Mazda, Tesla and Mercedes-Benz.)

The Rankings

This year, Toyota had the highest score for its supplier relations of the six automakers surveyed, with Honda close behind. Toyota has ranked No. 1 overall in the survey every year but two since the survey’s inception in 2001. Honda, which ranked first in 2009 and 2010 and was first this year in purchasing effectiveness, has consistently been a close second in recent years. However, both automakers’ scores dipped from last year, and General Motors strengthened its third-place ranking, increasing its score by 10 points.

On the lower end of the rankings, Nissan and Stellantis gained ground in supplier relations. Nissan actually outscored Ford, which dropped 23 points and fell to fifth place.

“We’re seeing how important the EV product cycle plan detail is, and communicating that to the supply base. Because, the suppliers are all looking for where their component sets play and where as a supplier is their position in the OEM’s long-term strategy,” says Dave Andrea, principal in Plante Moran’s Strategy and Automotive & Mobility Consulting Practice.

Here are some more takeaways from the survey, from Andrea and fellow Plante Moran automotive principal Mark Barrott.

Ford’s Divide

In March 2022, Ford announced a split of its internal combustion engine business (Blue Oval) from its electric-vehicle business (Model E). Suppliers expressed confusion around why components in their portfolios were categorized in one division or another as some components actually straddle both divisions. Knowing who to communicate with to get answers and results was also a problem. Andrea said Ford is still figuring out how to define and communicate the restructuring to both the supply base and within their own organization.

“Ford really illustrates the pressure that every purchasing group had between delivering on the short-term with material cost increase requests and supply chain disruption issues, along with communicating and executing their EV strategy,” Andrea says.

Ford positioned Model E as the future, and Blue Oval, “the transition to get us there,” says Andrea. “I think externally, from the supplier standpoint, their point is, ‘Well, I still make components that you need and I’m in Ford Blue now. Do I have a future with you or not?’”

The divisions were “just kind of put forward [by Ford] as: ‘This [Model] is the future. And this [Blue] isn’t the future.’” And they often don’t align with suppliers’ organizational structures, complicating decision-making.

'A Clear Roadmap'

Supplier satisfaction is closely related to the success of an OEM’s top-down internal communication of strategy, as well as healthy alignment of OEM engineering, manufacturing and purchasing departments. Purchasing staff, who deal directly with customers, must be well-informed of overarching company priorities and the tactical issues that OEM departments are dealing with so suppliers can make good product development decisions and anticipate problems or changes on the horizon. Purchasing agents also should have open channels of communication back to other departments to convey supplier issues and feedback.

“The best of all worlds is a clear roadmap where the company is going,” says Andrea. Without that clear picture, “a supplier can make an investment, and then that investment gets stranded. A capability that doesn’t get used—that’s a bad outcome. Another bad outcome is the supplier freezes and doesn’t make any investment, and then closer to a start of production to support a launch, that supplier is trying to catch up and go too fast.”

On the departmental side, “the worst is you have different agendas being played out,” says Andrea. If they don’t match up and they’re not supportive of each other, “that’s where you get the uncertainty, you get the friction, you get a higher cost to serve that individual customer.”

Nissan and GM have improved from previous WRI surveys in communicating their strategies and their platform architecture. “The suppliers know a bit better whether they fit,” says Andrea. “Nissan has been talking about their Ambition 2030 strategy and GM has certainly pushed forward their EV strategy with their Ultium battery technology and vehicle architecture strategy.”

Where’s the Crisis Management Now?

During the pandemic, automakers assembled “war rooms” to tackle supply chain, workforce and even existential crises collectivity and in unison. Andrea says that automakers would be well-served applying a similar crisis mindset—not unlike a continuous improvement mindset—during the EV shift.

“Industry is very good at reacting to crises,” he says. “There’s a common enemy and everybody comes together. And that’s what we need day in and day out. That common enemy is the uncertainty that’s in the marketplace, whether it's on the product-demand front in terms of what products are being demanded, or on the regulatory front in terms of knowing what vehicles and powertrain combinations can be sold in a regulatory environment. You face that uncertainty every day, and you just pick at it every day—a little here, a little there—and it adds up.”

Barrott singled out GM as continuing to work more collaboratively at a higher level, with a command center staffed by leaders in all the different functional areas. “I think some of their results in the semiconductor crisis bear that out,” he says.

Stepping up Purchasing Training

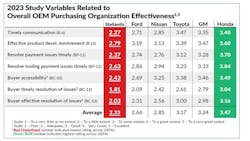

Scores have plummeted in recent years on a survey question that asks suppliers to judge how well their buyer knows how their part works in a vehicle and the technology around it. This indicates that purchasing staff needs more training in new technology, says Andrea. “When you think of castings and forgings and stampings and those kind of parts, the industry has been buying them for hundreds of years. Now that we have batteries and all these new technologies, people have to be trained on them and how to buy them and what the cost models are.”

Disgruntlement also builds when OEMs expand purchasing duties to cover EVs as well as ICEs. Rather than hiring additional people, “they try to have one person do two jobs,” says Andrea. “That puts tremendous pressure on that one individual.”

And then there’s the “churn” factor—bringing in lots of new people into purchasing, evidenced by falling scores on purchasing agents’ basic commercial knowledge. “Things like, how do you move a purchase order through, how do you get terms and conditions moved for you? Those numbers went down,” says Andrea.

“It goes back to there being so much disruption and so much going on in the industry right now that the pipeline is fixed,” says Andrea. “You’re trying to do more decision-making and more issues are coming and unless you grow that pipeline—whether it’s by the skills of the individuals or even technology tools—your numbers are going to go down because until you fix that pipeline, you’re trying to force more through it.”